The

yoga world is on fire. Or at least it should be. Yoga has become international.

Yoga has become a household word. Yoga has become scandalous. And recently, in

the wake of repeated events of sexual misconduct (and worse) among prominent national

and international yoga teachers, practitioners of yoga are questioning, defending,

or renouncing their practice. While the circumstances that led to this

questioning are unfortunate, I am glad that people are beginning to question

the legitimacy and the hagiography of yoga, in particular Modern Postural Yoga.

There is, in its beginning stages, a movement to redefine yoga in its modern

context. Finally!

But, wait. Oddly enough, this is

what has been going on in the world of yoga all along. Redefining and reforming

tradition has been a central theme in the evolution of yoga for at least 3,000

years. The modern posture-centric versions of yoga that people are now seeking

to redefine are only the most recent in a long line of iterations of yoga. Let

me back up a bit.

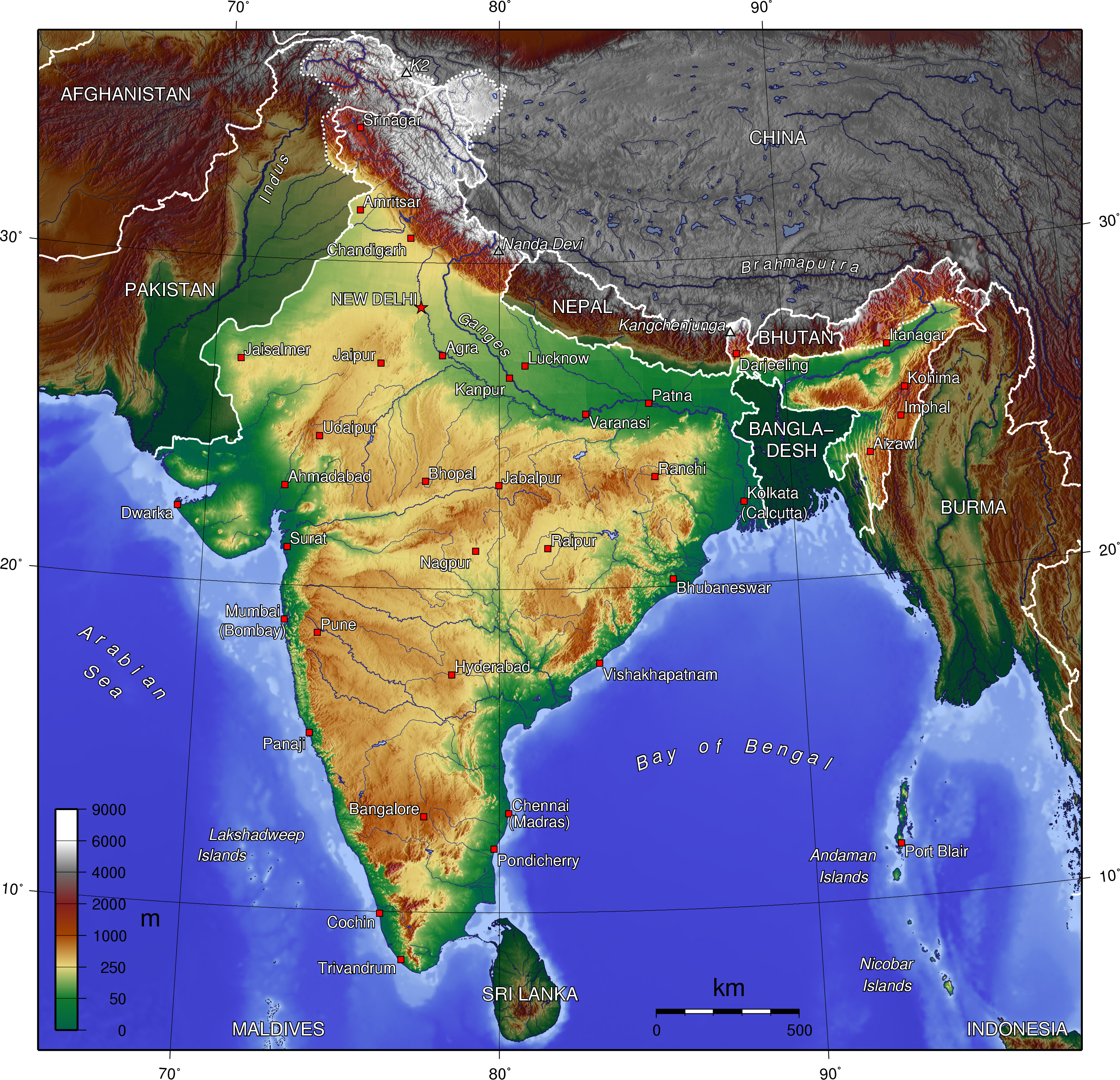

I was on the coast of Kerala

(Southwest India) when I first saw someone performing one of the series of Pattabhi

Jois’s Asthanga yoga. I had been in India for several years at that point,

exploring all manner of yogic practices. In my travels thus far I had lived and

studied with dozens, if not hundreds, of monks and yogis from all over India,

but I had never seen anything like what this Argentinian man was doing each morning

on the roof of this Kerala Ashram. After a few days, I asked him where he

learned that amazing fusion of yoga and gymnastics. “This is yoga,” he told me,

“This is the real yoga.” Hmmm. I wasn’t so sure. This man was certain that his

system was the one true yoga, and yet of all the yogas that I had seen and

practiced, this was my first and only contact with this method.

Now, India is big,

like – really big. Stretching 2,000 miles North to South, and nearly another 2,000

miles East to West, India is vast and labyrinthine and ancient. So, though I

had met no other yogi who referenced anything like this acrobatic yoga, it was

quite possible that I had missed something. I spent some time learning the

first and second series (the beginning sequences in Pattabhi Jois’s system) from

this talented and generous man, and then I tried out that style of practice for

a few months. I never did find a lineage of yogis in India who used that method

of poses and sequences, but I liked the athleticism it engaged. Recent

scholarship by Mark Singleton has done much to shed light on the absence in India of any yogic system

similar to those developed by Krishnamacharya and his students. The short version is that Krishnamacharya's yoga systems were actually a hybrid of various of Indian yogas combined with European derived fitness exercises. Thus, it was a new iteration of yoga: ancient tradition mixing with contemporary methods. If you look deep enough, this theme of hybridization stretches all the way back to the origins of yoga. In any case there definitely were yoga asanas being practiced elsewhere

and independently in India. And so I continued practicing hatha yoga in the ways

that I had learned from other teachers, and I enjoyed my practice.

But learning hatha

yoga from yogis in India was a lot more difficult than one would think. This

was because the yogas of the sadhus and renunciates in India have been primarily

variations on meditative methods, the most popular of which was Bhakti yoga, or

the yoga of devotion. During my years in India, I made it a point to seek out

places that were out of the way; in other words, places where Westerners weren’t.

My goal was to taste and learn from authentic practitioners, which I had

learned, were usually the quiet ones in out of the way places. What I found was

that very few yogis had much of an asana practice at all. When it became known to

them that I practiced hatha yoga, I was often looked at with a combination of pity

and disdain, or warned against the practice, or both.

The warnings generally fell into

two categories: the “Hatha yoga is too rough” category, and the “Hatha yoga is

fruitless and will get you nowhere” category. The former warning was most

common among Sannyasins (the orange robe wearing initiates common in the Dasanami sects),

but I received a version of that same warning from most Mahayana and Theravadan

Buddhist monks I came across as well. The latter, “Hatha yoga is fruitless” warning I

got mostly from sadhus and renunciates who had long ago left the comfort of

ashrams for the simplicity and intimacy of the wandering life. Keep in mind,

these were ascetics who were warning me away from the overly “hard and

forceful” practices of hatha yoga. There is a whole discussion as to why they

felt this way, but we’ll save that for another day. In general, these yogis

would each have an asana or two that they used for meditative practices, but

they rarely devoted time specifically to asana practice. Their yoga consisted

of hours of meditative absorption and other sadhana (practice), usually

involving daily rituals. To be fair, when I told people that I practiced hatha

yoga, there were also quite a few comments along the lines of: “I should be

doing that,” and, “Can you show me how to…” and, “Do you have any exercise for…”

But that line of response was limited to householders: people from outside the

realm of yogis and sadhus looking in.

The warnings generally fell into

two categories: the “Hatha yoga is too rough” category, and the “Hatha yoga is

fruitless and will get you nowhere” category. The former warning was most

common among Sannyasins (the orange robe wearing initiates common in the Dasanami sects),

but I received a version of that same warning from most Mahayana and Theravadan

Buddhist monks I came across as well. The latter, “Hatha yoga is fruitless” warning I

got mostly from sadhus and renunciates who had long ago left the comfort of

ashrams for the simplicity and intimacy of the wandering life. Keep in mind,

these were ascetics who were warning me away from the overly “hard and

forceful” practices of hatha yoga. There is a whole discussion as to why they

felt this way, but we’ll save that for another day. In general, these yogis

would each have an asana or two that they used for meditative practices, but

they rarely devoted time specifically to asana practice. Their yoga consisted

of hours of meditative absorption and other sadhana (practice), usually

involving daily rituals. To be fair, when I told people that I practiced hatha

yoga, there were also quite a few comments along the lines of: “I should be

doing that,” and, “Can you show me how to…” and, “Do you have any exercise for…”

But that line of response was limited to householders: people from outside the

realm of yogis and sadhus looking in.

These days, with Baba Ramdev on

Indian TV on a daily basis, the Indian views on yoga have shifted dramatically.

And here we see yet another transformation in the development of yoga taking place in India's not insignificant “take back yoga” movement, which utilizes the recent advancements made by the (very much western influenced) asana-focused Modern Postural Yoga and reintegrates them with sectarian Hindu practices. In the West, after decades of growing popularity, yoga is now staggering under a

growing laundry list of sexual misconduct by high profile gurus. Awkwardly, this

misconduct has been going on for decades, and it is unfortunately not limited

to those big name yogis who are now in the news. There is an inherent trap in

the guru disciple relationship that bends that relationship into an ever

greater imbalance, and thus situations like the Mangrove Mountain or Bikram Choudry abuses of sex and power are not uncommon. Add to these scandals the recent

deaths of the primary progenitors of Modern Postural Yoga (Pattabhi Jois – 2009,

B.K.S. Iyengar – 2014), and it is natural that the yoga community is beginning

to seriously question: “Where do we go from here?”

But, before we can answer that, we need to address two things:

1) Where are we now – where is the practice of yoga now?

There are many levels to this question, all of which are important.

2) How did we get here – how did the practice of yoga get to

be the way it is today?

And, in answering the second question, we can discover the

answer to the big elephant in the room questions; those key questions that have

for decades wilted under the intense glare of orthodoxy: What actually is yoga? How do

we practice it? How do we teach it? And how do we learn it?